Children and teens react, in part, to what they see from the adults around them. When parents and caregivers deal with the COVID-19 calmly and confidently, they can provide the best support for their children. Parents can be more reassuring to others around them, especially children, if they are better prepared. In order to be prepared, we urge you to gather your information from credible sources such as:

www.ckphu.com , https://www.cdc.gov/ , https://cmha.ca/ , https://www.who.int/

Not all children and teens respond to stress in the same way. Some common changes to watch for include:

- Excessive crying or irritation in younger children

- Returning to behaviours they have outgrown (for example, toileting accidents or bedwetting)

- Excessive worry or sadness

- Unhealthy eating or sleeping habits

- Irritability and “acting out” behaviours in teens

- Poor school performance or avoiding school

- Difficulty with attention and concentration

- Avoidance of activities enjoyed in the past

- Unexplained headaches or body pain

- Use of alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs

There are many things you can do to support your child:

- Take time to talk with your child or teen about the COVID-19 outbreak. Answer questions and share facts about COVID-19 in a way that your child or teen can understand (make sure you are getting your information from credible sites such as www.ckphu.com)

- Reassure your child or teen that they are safe. Let them know it is ok if they feel upset. Share with them how you deal with your own stress so that they can learn how to cope from you.

- Limit your family’s exposure to news coverage of the event, including social media. Children may misinterpret what they hear and can be frightened about something they do not understand. The unknown is frightening for all of us, especially our children.

- Try to keep up with regular routines. If schools are closed, create a schedule for learning activities and relaxing or fun activities.

- Be a role model. Setting a good example for your children by managing your stress through healthy lifestyle choices, such as eating healthy, exercising regularly, getting plenty of sleep, and avoiding drugs and alcohol, is critical for parents and caregivers. When you are prepared, rested, and relaxed you can respond better to unexpected events and can make decisions in the best interest of your family and loved ones.

The amount of damage caused from something like COVID-19 can be overwhelming. The separation from school, family, and friends can create a great amount of stress and anxiety for children.

The emotional impact of an emergency on a child depends on a child’s characteristics and experiences, the social and economic circumstances of the family and community, and the availability of local resources. Not all children respond in the same ways. Some might have more severe, longer-lasting reactions. The following specific factors may affect a child’s emotional response:

- Direct involvement with the emergency

- Previous traumatic or stressful event

- Belief that the child or a loved one may die

- Loss of a family member, close friend, or pet

- Separation from caregivers

- Chronic illness

- How parents and caregivers respond

- Family resources

- Relationships and communication among family members

- Repeated exposure to mass media coverage of the emergency and aftermath

- Ongoing stress due to the change in familiar routines and living conditions

- Cultural differences

- Community resilience

The following tips can help reduce stress before, during, and after COVID-19 hits Chatham-Kent.

Before

Talk to your children so that they know you are prepared to keep them safe. Help them understand that things are constantly changing and that you understand that the fear of the unknown can cause anxious feelings.

Review safety plans before a disaster or emergency happens. Having a plan will increase your children’s confidence and help give them a sense of control.

During

Stay calm and reassure your children.

Talk to children about what is happening in a way that they can understand. Keep it simple and appropriate for each child’s age.

You can help your children feel a sense of control and manage their feelings by encouraging them to take action directly related to the pandemic. For example, children can help others by connecting with friends and neighbours online and at a safe distance to see how they are doing, volunteering to deliver groceries to the porches of their elderly neighbours, make cards for healthcare professionals, shut-ins and people in nursing homes. Children should NOT participate in caregiving activities for sick parents for health and safety reasons.

After

Provide children with opportunities to talk about what they went through or what they think about it. Encourage then to share concerns and ask questions.

It is difficult to predict how some children will respond to disasters and traumatic events. Because parents, teachers, and other adults see children in different situations, it is important for them to work together to share information about how each child is coping after a traumatic event.

If, after this is all behind us, your child continues to be consumed with worry, speak to your doctor or mental health professional.

Common Reactions

The common reactions to distress will fade over time for most children. Children who were directly exposed to a disaster can become upset again; behaviour related to the event may return if they see or hear reminders of what happened. If children continue to be very upset or if their reactions hurt their schoolwork or relationships then parents may want to talk to a professional or have their children talk to someone who specializes in children’s emotional needs.

For infants to 2 year olds

Infants may become crankier. They may cry more than usual or want to be held and cuddled more.

For 3 to 6 year olds

Preschool and kindergarten children may return to behaviours they have outgrown. For example, toileting accidents, bed-wetting, or being frightened about being separated from their parents/caregivers. They may also have tantrums or a hard time sleeping.

For 7 to 10 year olds

Older children may feel sad, mad, or afraid that the event will happen again. Peers may share false information; however, parents or caregivers can correct the misinformation. Older children may focus on details of the event and want to talk about it all the time or not want to talk about it at all. They may have trouble concentrating.

For preteens and teenagers

Some preteens and teenagers respond to trauma by acting out. This could include reckless driving, and alcohol or drug use. Others may become afraid to leave the home. They may cut back on how much time they spend with their friends. They can feel overwhelmed by their intense emotions and feel unable to talk about them. Their emotions may lead to increased arguing and even fighting with siblings, parents/caregivers or other adults.

For special needs children

Children who need continuous use of a breathing machine or are confined to a wheelchair or bed, may have stronger reactions to a threatened or actual disaster. They might have more intense distress, worry or anger than children without special needs because they have less control over day-to-day well-being than other people. The same is true for children with other physical, emotional, or intellectual limitations. Children with special needs may need extra words of reassurance, more explanations about the event, and more comfort and other positive physical contact such as hugs from loved ones.

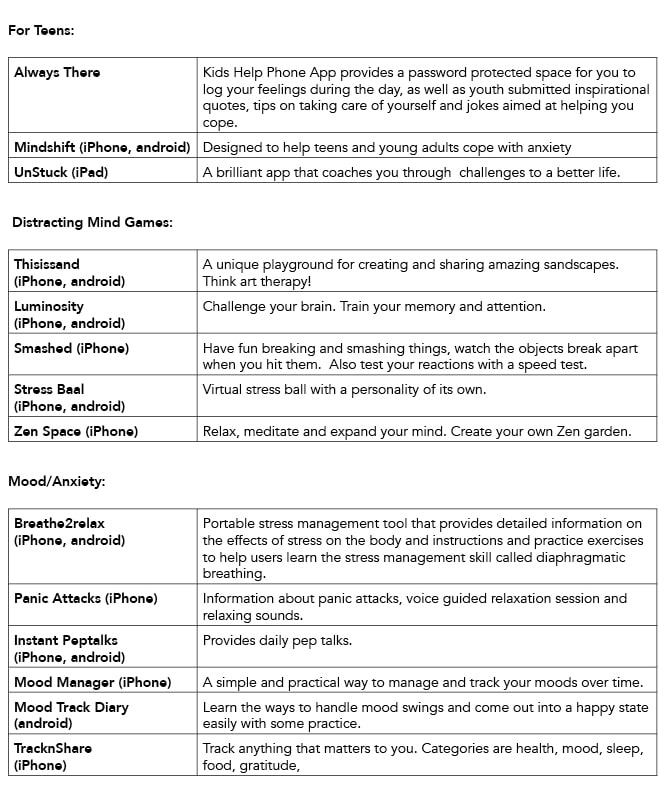

Mental Health Apps that may help:

These apps are not meant to replace professional care (doctor, counselor, social worker, therapist, etc)

Please find a complete list of mental health resources at ckphu.com